The Strongest Lightning Strikes Not From Dark Skies

As the Olympian gods struggle to make sense of the end of their empire, a rebellion is rising from the valley below. The film examines how the forces of power often fail to recognize the frailty of their rule, while the oppressed and the organized find their capacity to strike need not wait for the confluence of an imagined perfect storm. The script is written in dactylic hexameter—the meter of Greek epic—and borrows heavily from the Brechtian style and ethos of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, lending a classical strangeness to the performances.

-

In 1839, Karl Marx, who was just 21 years old, wrote the first act of an unfinished play titled Oulanem. In it, a strange, messianic character comes to visit a small alpine town and while sequestered in a hostel, turns over the destruction of the world in his mind. Meanwhile, his comrade, Lucindo, has fallen for a local woman named Beatrice, who pronounces her own sudden, unexpected love for him, saying: “the strongest lightning strikes not from dark skies.”

I like this phrase, not just for its romantic content, but for how it also describes a surprisingly common political event: when upheaval and revolt seem to take the world by surprise. Whether by self-delusion or misapprehension, the forces of power often fail to recognize the frailty of their rule, while the oppressed and the organized find their capacity to strike need not wait for the confluence of an imagined perfect storm.

The Strongest Lightning is about how those with ultimate power—the Olympians—experience the shock of defeat. This state of panic, rage, and incomprehension is today, everywhere: from the top ranks of the Israeli Defense Forces to the top ranks of the Democratic party. Our elites may lack the ultimate power of those who reside at the summit of Mount Olympus, but their sense of entitlement and superiority are just as rarefied.

To emphasize the gap between power and understanding, to render it unfamiliar—most of the script for The Strongest Lightning is written in dactylic hexameter, the meter of Greek epic. Despite its foundational place in Western literature, this metrical form can sound totally alien and unnatural when used in English and I’ve aimed to further heighten this strangeness by asking the actors to do their best to simply read the script, rather than perform it or to try to inhabit the characters. The challenge of the film—for both the actors and audience—is to resist the temptation to smooth out the awkward enjambments and, instead, let the meter rule. Of course, no true challenge is without a struggle and at some points the meter breaks down, as do the color assignations that map the actors to the statues. A film about the frailty of a given rule cannot, by its nature, simply follow the rules—even ones that it sets out for itself.

The film’s characterization of Herakles is indebted to the writer Peter Weiss, whose three-part novel, The Aesthetics of Resistance begins by retelling the myths of Herakles as a proletarian hero. In Weiss’ version the demigod wins his true power by living among mortals, witnessing their deaths, and adopting their struggles as his own. This vision of the power of mortal life, when compared with the immortality of the gods, also appears in Cesare Pavese's Dialogues with Leucò and its film adaptation From the Clouds to the Resistance, directed by Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub.

Straub and Huillet always resisted the core ideological principle of cinema, namely that “seeing is believing” and they similarly also aimed to undermine the so-called truths we hear with our own ears. To do this in From the Clouds to the Resistance, they chose to have their actors read their lines with a halting, disruptive cadence, one that would resist the pull of naturalism. Such a tactic is both simple and hard-won: they would conduct long rehearsals and were incredibly demanding of their actors, insisting each word be delivered with a specific force and intonation. It’s no surprise that these techniques have not been picked up by very many other filmmakers.

But in this film I wanted to attempt just that. So we worked with an archaic metrical form and instead of casting actors, chose the poets Wayne Koestenbaum, James Loop, Sahar Muradi, Claire DeVoogd, Rami Karim and tilghman alexander goldsborough. They are all exceptional performers who have a well-attuned sense of the power of non-naturalistic speech. The film succeeds through their uncanny ability to work to the rule of the meter.

*

Marx never completed Oulanem and, in fact, never wrote another play. But his romantic phrase that I chose as the title for this film suggests that revolution and love share the power of sudden, magnificent disequilibrium. I hope the film accomplishes something similar through its formal choices, both visual and textual. And while the bolt from the blue cannot, by definition, be predicted, we can be assured that it will, eventually, make contact.

Nate Lavey

January 2025

-

THE PRIEST: Please do not damage me, deathless ones, timeless ones, dreaming. Hear this!

APHRODITE: Voice here, where silence was. What are you, crouched in clay, shaking?

THE PRIEST: Mortal. I serve you, my goddess. I climbed up from Athens, afire—look.

APHRODITE: Mortal? The noise of calamity taints our sleep, smoke wafts on our rare thin air, its tang, we can taste it. Speak of the traitor, our brother.

THE PRIEST: This is the weather: A storm is now gathering—not above, but below. Tranquil, yet buoyed by wrath; in its quiet hides impossible rupture. Look down! Look! Gods, I beg you: it’s the end of the world. The mountain will crumble.

ARTEMIS: Weather? When rain has approached me, its fingers caressing and hesitant, That is because I invited it kiss me. The hurricane, my pet, crawls on its belly when I call it near. Man, we are gods! When this feast ends, Whether by flood or by fire, it will end on our gesture. You blaspheme!

THE PRIEST: Goddess, the people of Athens have slaughtered Theseus the great king. Temples they’ve toppled; your altars become their tables, their beds, chairs; offerings shared out among them; now the mass charge up Olympus – Feel how the flanks of the mountain are shuddering with their coming. Now you must run where they cannot live: far moons, asteroids, void stars.

DIONYSUS: Capture Olympus Impossible. Our law is the glacier, the volcano, darkness and light. We’ve made six lively worlds, breathed them full of the quick, five we’ve destroyed. This one spins at our pleasure.

THE PRIEST: But by the soles of their feet, they will make this thing possible. Change comes.

ARTEMIS: What is impossible to gods is impossible to history. We are...

APHRODITE:...What is.

THE PRIEST: Hear it, great goddess, like drumbeats. That thunderbeat is them.

HERMES: No passing man makes the mountain quake. We will not fly from these be-ings, Death their one property, who would take what is ours, the domed world we built.

*

APHRODITE: What of our brother, the half-god, who left our Olympus, walked away?

THE PRIEST: Herakles turned, he’s forsaken you. He champions the people and their cause. Dressed in the skin of a lion, he comes, savage—he drags the rough club.

ARTEMIS: Blocks of the sky, speed, sink down! Let the stones froth, float up, and the sea—shatter.

DIONYSUS: Not only altars or hecatombs! The fates, our industrious, precise sisters, they desecrate. Climbing they mean to climb out of their fortune. Priest, make them bear the divine, look again at the light, be appalled!

HERMES: Show them: the divine is not only their ruler, but the meaning of their short lives. Timeless, we hold the time, both its grains, and its flow, that holds them. There is no outside to us, our dominion, no existence without us.

APHRODITE: Always us, what is, has been. The continuous past, then, the forever.

HERAKLES: The cities, the forests, the roads, the seas, the fields are no longer yours to possess. People—your subjects, that red, teeming sublime —have already destroyed your power. The strongest lightning strikes not from dark skies.

APHRODITE: Herakles, traitor, are you here? — destroyer, omega, to eat the world?

HERAKLES: What world? There are many. Sister, I am here because they are here, gathered just below the summit of Olympus. They will seize this hill, which has always been theirs.

HERMES: How can you join them, Herakles? You are divine, by the god half. Reason dissolves in the face of this treachery—you’d rather the man half?

HERAKLES: True, brother, I share a past with you, but the people hold my life now. When I freed Prometheus from the rock, I cracked; I became vulnerable to the savor of something more than divine. It troubled me. So I wandered the roads; I talked with fugitives, peasants, the enslaved.

*

HERAKLES: In the streets of Thebes I met women who taught me the taste of bread, the weight of a tear, the steps to dance. I went to parties where people screamed with laughter, to funerals where they screamed with grief, I drank all night, I witnessed people trampled into the dirt, I witnessed others grasp, for a second, joy, I found myself the butt of the joke, I hungered, I heard music. I saw death from the eyes of the living, felt myself scoured by it, made clean, and fragile. On the shores of Okeanos, I made friends who built tools and instruments; they put these in my hands, and I learned to think the unthinkable. A reason that cannot be grasped from the palace.

ARTEMIS: Flooding, these clouds I see, blanketing the slopes like a dark swarm, but——people, it can’t be. We are their life—are life. Without us, they are just death, shod in boots, living time without length, breathe, buzz then sink earthwards immediately, feed the new insects, turn to grass, brown, seed, die again. I merely smile, they are already cows in the field: they low, chew.

HERAKLES: Shortness gives their lives form.

HERMES: Our state is fixed beyond any state. How have they dreamed this rebellion, they who think only in fragments? Wholeness always eluding them, its grandeur, curved on the bell of all matter?

HERAKLES: The act of revolt is the advance guard of the idea. Its rationale exists in its practice, in its fragments, its multiplicity. The whole is shared, in many bodies, many lives. It becomes the world as it becomes lived.

APHRODITE: Fragmenting—yes, I have seen people torn. I have summoned the peaked wave, Watched as it towered, and seemed to be thinking, then swallow groaning ships whole. Seen their grey faces, their eyes turned for the sky, their terror at death. They will not come. They have nothing but bodies to throw at our power. If they come, by our power their bodies will fall.

HERAKLES: That is their miracle: only an empty hand can form a fist. The old laws dissolve before the new. Your timeless justice will be buried in the masses.

DIONYSUS: These masses...what are they?

HERAKLES: They are Nothing.

DIONYSUS: What do they want?

HERAKLES: Everything.

DIONYSUS: What can they do?

HERAKLES: Something.

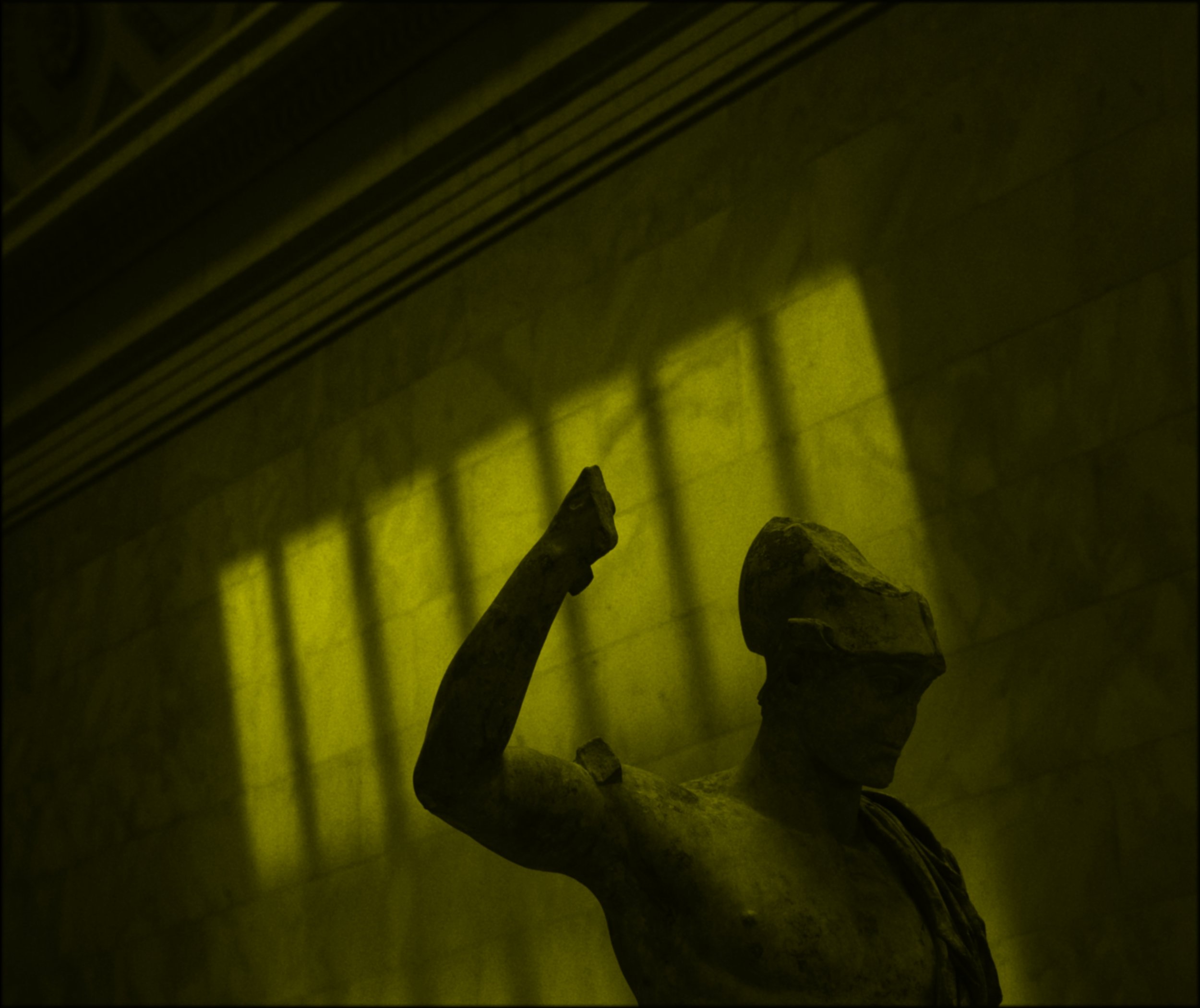

High-resolution stills & production photos ↴

Download all images here.

Credit: Guy Greenberg

Credit: Guy Greenberg

Credit: Guy Greenberg

Credit: Guy Greenberg

Credit: Guy Greenberg

For more information: